Abstinence Violation Effect AVE What It Is & Relapse Prevention Strategies

It can also support the development of healthier attitudes toward lapses and the possibility of relapse at some point in time. Thus, while it is vital to empirically test nonabstinence treatments, implementation research examining strategies to obtain buy-in from agency leadership may be just as impactful. For example, offering nonabstinence treatment may provide a clearer path forward for those who are ambivalent about or unable to achieve abstinence, while such individuals would be more likely to drop out of abstinence-focused treatment. To date there has been limited research on retention rates in nonabstinence treatment.

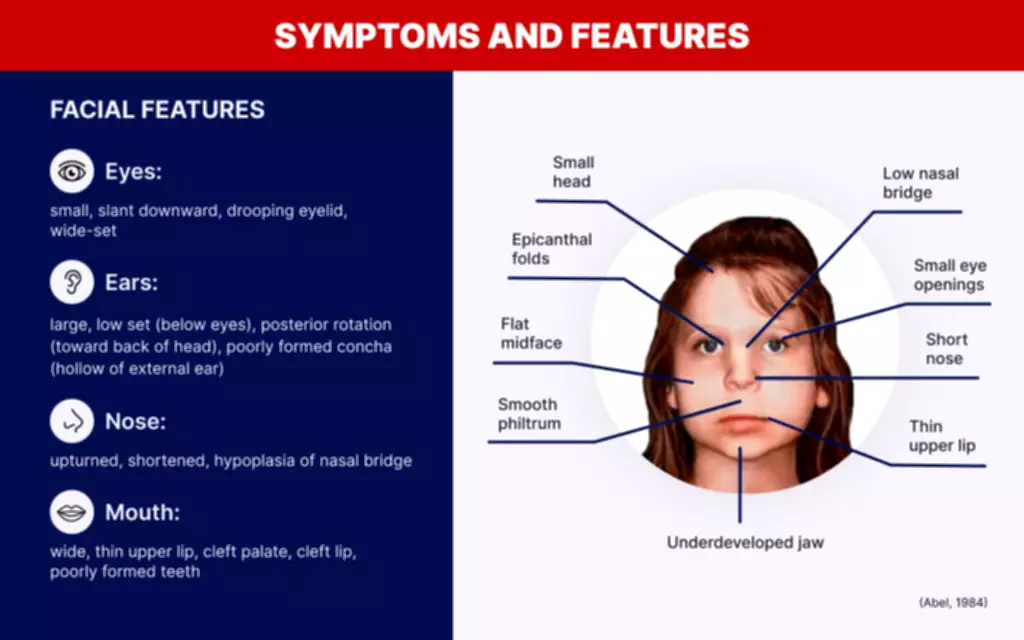

Cognitive Behavioural model of relapse

The use of functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) techniques in addictions research has increased dramatically in the last decade 131 and many of these studies have been instrumental in providing initial evidence on neural correlates of substance use and relapse. In one study of treatment-seeking methamphetamine users 132, researchers examined fMRI activation during a decision-making task and obtained information on relapse over one year later. Based on activation patterns in several cortical regions they were able to correctly identify 17 of 18 participants who relapsed and 20 of 22 who did not. Functional imaging is increasingly being incorporated in treatment outcome studies (e.g., 133) and there are increasing efforts to use imaging approaches to predict relapse 134. While the overall number of studies examining neural correlates of relapse remains small at present, the coming years will undoubtedly see a significant escalation in the number of studies using fMRI to predict response to psychosocial and pharmacological drug addiction treatments. In this context, a critical question will concern the predictive and clinical utility of brain-based measures with respect to predicting treatment outcome.

Sign up for text support

But if they still have drugs left, they decide to go ahead and deplete their supply before quitting again. CP conceptualized the manuscript, conducted literature searches, synthesized the literature, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. SD assisted with conceptualization of the review, and SD and KW both identified relevant literature for the review and provided critical review, commentary and revision. RP has also been used in eating disorders in combination with other interventions such as CBT and problem-solving skills4.

- Substance use recovery programs should refrain from defining a mere slip as a total failure of abstinence.

- In particular, given recent theoretical revisions to the RP model, as well as the tendency for diffuse application of RP principles across different treatment modalities, there is an ongoing need to evaluate and characterize specific theoretical mechanisms of treatment effects.

- Marlatt, in particular, became well known for developing nonabstinence treatments, such as BASICS for college drinking (Marlatt et al., 1998) and Relapse Prevention (Marlatt & Gordon, 1985).

Unconditional Positive Regard

- This does not mean that 12-step is an ineffective or counterproductive source of recovery support, but that clinicians should be aware that 12-step participation may make a client’s AVE more pronounced.

- Despite these obstacles, SSPs and their advocates grew into a national and international harm reduction movement (Des Jarlais, 2017; Friedman, Southwell, Bueno, & Paone, 2001).

- Using a person-centered, strengths-based approach and unconditional positive regard, counselors should affirm clients’ efforts to continue in recovery and encourage them to reflect on their goals and how the recurrence could be an opportunity to gain greater insight and adjust their action plan.

Moreover, people who have coped successfully with high-risk situations are assumed to experience a heightened sense of self-efficacy (i.e., a personal perception of mastery over the specific risky situation) (Bandura 1977; Marlatt et al. 1995, 1999; Marlatt and Gordon 1985). Conversely, people with low self-efficacy perceive themselves as lacking the motivation or ability to resist drinking in high-risk situations. The current review highlights a notable gap in research empirically evaluating the effectiveness of nonabstinence approaches for DUD treatment.

Cues for Health and Well-Being in Early Recovery

- This type of policy is increasingly recognized as scientifically un-sound, given that continued substance use despite consequences is a hallmark symptom of the disease of addiction.

- If you prefer receiving this type of support from the comfort of your own home, you might consider working with a therapist virtually.

- Early attempts to establish pilot SSPs were met with public outcry and were blocked by politicians (Anderson, 1991).

- Instead, the literature indicates that most people with SUD do not want or need – or are not ready for – what the current treatment system is offering.

- Regardless of setting and training, counselors working with clients who are in or considering recovery can provide support by helping them build their strengths, resiliencies, and resources.

- Make warm handoffs when transferring clients to other providers or recovery communities.

Relapse poses a fundamental barrier to the treatment of addictive behaviors by representing the modal outcome of behavior change efforts 1-3. For instance, twelve-month relapse rates following alcohol or tobacco cessation attempts generally range from 80-95% 1,4 and evidence suggests comparable relapse trajectories across various classes of substance use 1,5,6. Preventing relapse or minimizing its extent is therefore a prerequisite for any attempt to facilitate successful, long-term changes in addictive behaviors.

1.1. Harm reduction treatments specific to alcohol use disorder

It is inevitable that the next decade will see exponential growth in this area, including greater use of genome-wide analyses of treatment response 109 and efforts to evaluate the clinical utility and cost effectiveness of tailoring treatments based on pharmacogenetics. Finally, an intriguing direction is to evaluate whether providing clients with personalized genetic information can facilitate reductions in substance use or improve treatment adherence 110,111. The last decade has seen a marked increase in the number of human molecular genetic studies in medical and behavioral research, due largely to rapid technological advances in genotyping platforms, decreasing cost of molecular analyses, and the advent of genome-wide association studies (GWAS). Not surprisingly, molecular genetic approaches have increasingly been incorporated in treatment outcome studies, allowing novel opportunities to study biological influences on relapse. Given the rapid growth in this area, we allocate a portion of this review to discussing initial evidence for genetic associations with relapse.

Abstinence Violation Effect (AVE)

Although some high-risk situations appear nearly universal across addictive behaviors (e.g., negative affect; 25), high-risk situations are likely to vary across behaviors, across individuals, and within the same individual over time 10. Whether a high-risk situation culminates in a lapse depends largely on the individual’s capacity to enact an effective coping response–defined as any cognitive or behavioral compensatory strategy that reduces the likelihood of lapsing. Based on the cognitive-behavioral model of relapse, RP was initially conceived as an outgrowth and augmentation of traditional behavioral approaches to studying https://ecosoberhouse.com/ and treating addictions. The evolution of cognitive-behavioral theories of substance use brought notable changes in the conceptualization of relapse, many of which departed from traditional (e.g., disease-based) models of addiction. Cognitive-behavioral theories also diverged from disease models in rejecting the notion of relapse as a dichotomous outcome. Rather than being viewed as a state or endpoint signaling treatment failure, relapse is considered a fluctuating process that begins prior to and extends beyond the return to the target behavior 8,24.

- His issue with drinking led to a number of personal problems, including the loss of his job, tension in his relationship with his wife (and they have separated), and legal problems stemming from a number of drinking and driving violations.

- It is inevitable that everyone will experience negative emotions at one point or another.

- After six successful months of recovery, Joe believed he was well on his way to being sober for life; however, one evening, he got into a major argument with his wife regarding her relationship with another man.

- The dynamic model of relapse assumes that relapse can take the form of sudden and unexpected returns to the target behavior.

AVE in the Context of the Relapse Process

Results indicated that RP was generally effective, particularly for alcohol problems. Specifically, RP was most effective when applied to alcohol or polysubstance use disorders, combined with the adjunctive use of medication, and when evaluated immediately following treatment. Moderation analyses suggested that RP was consistently efficacious across treatment modalities (individual vs. group) and settings (inpatient vs. outpatient)22. Another factor that may occur is the Problem of Immediate Gratification where the client settles for shorter positive outcomes and does not consider larger long term adverse consequences when they lapse. This can be worked on by creating a decisional matrix where the pros and cons of continuing the behaviour versus abstaining are written down within both shorter and longer time frames and the therapist helps the client to identify unrealistic outcome expectancies5.

For example, one could imagine a situation whereby a client who is relatively committed to abstinence from alcohol encounters a neighbor who invites the client into his home for a drink. Feeling somewhat uncomfortable with the offer the client might experience a slight decrease in self-efficacy, which cascades into positive outcome expectancies about the potential effects of having a drink as well as feelings of shame or guilt about saying no to his neighbor’s offer. Importantly, this client might not have ever considered such an invitation as a high-risk situation, yet various contextual factors may interact to predict a lapse. Efforts to develop, test and refine theoretical models are abstinence violation effect critical to enhancing the understanding and prevention of relapse 1,2,14. A major development in this respect was the reformulation of Marlatt’s cognitive-behavioral relapse model to place greater emphasis on dynamic relapse processes 8. Whereas most theories presume linear relationships among constructs, the reformulated model (Figure 2) views relapse as a complex, nonlinear process in which various factors act jointly and interactively to affect relapse timing and severity.